Anti-Chinese rhetoric in San Francisco and throughout the American West culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Japanese immigrants also faced hostility; by 1924, the exclusionary policy was expanded to include quotas that further restricted the entry of immigrants seen as nonwhite.

Anti-Chinese rhetoric in San Francisco and throughout the American West culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Japanese immigrants also faced hostility; by 1924, the exclusionary policy was expanded to include quotas that further restricted the entry of immigrants seen as nonwhite.

View full album

Both the Chinese and Japanese immigrants, Buddhist or not, encountered anti-Asian ordinances and general hostility at the local level. Anti-Chinese rhetoric and violence erupted repeatedly throughout the 1850s and 1860s. The first major anti-Chinese riot in San Francisco was in 1866. In the early 1870s the city of San Francisco passed ordinances prohibiting the use of firecrackers and Chinese ceremonial gongs, both of which played important roles in Buddhist and Daoist ceremonies. The campaign intensified in the late 1870s, culminating in the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which suspended immigration of Chinese workers for ten years and made the Chinese ineligible for naturalization as citizens. Not only were workers prohibited, but Chinese women who might have enabled the workers already in America to settle down into family life were also barred from immigrating. The Chinese population of the United States dwindled, though many workers who could not afford to return to China found themselves stranded thousands of miles from their families.

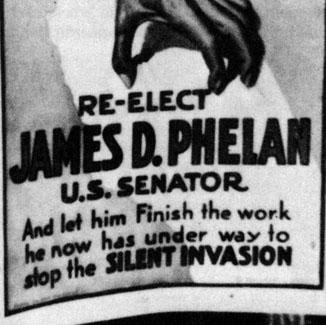

By the end of the century, the exclusion policy was reaffirmed and expanded to include other “Asiatics." Despite the concerted efforts of the Japanese to assimilate, there was an also anti-Japanese movement. By 1924, a new wave of anti-immigrant and anti-Asian sentiment set quotas on all immigration and prohibited the entry of all people not eligible for citizenship, which included the Chinese and Japanese. The general hostility toward East Asians was exhibited not only because of their race, but because of their perceived “alien” customs and religious practices. Second and third generation Chinese and Japanese, wishing to assimilate more fully into American life, gradually abandoned the temples. It was, however, in terms of their “nonwhite” race that the exclusion from citizenship was cast.